Travel spreads the virus more quickly

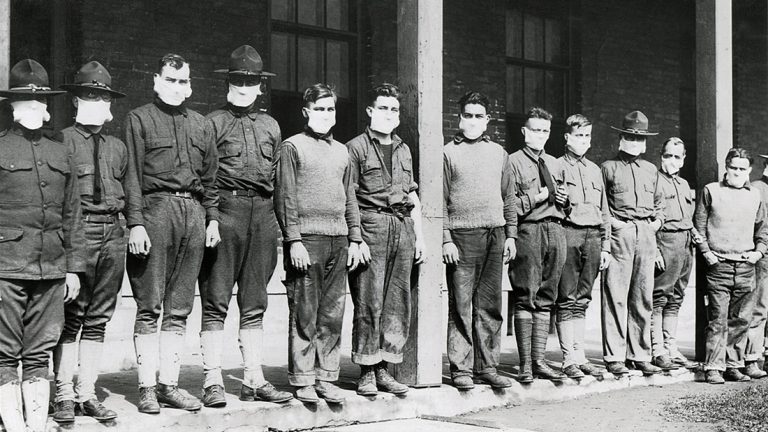

In 1918, it took a person at least two days to travel across the United States by railroad. Today, a person can circumnavigate the entire planet by jet plane in forty-five hours– just slightly less than the same two days. Given the slow travel time of our ancestors, the rate of geographic spread was likely slowed; however, longer periods of time in close quarters with fellow travelers, likely resulted in a higher rate of community spread. So, when soldiers finally reached their destination back home or back on the front lines, there were more carriers of the virus. Had the world not been engaged in a major war, requiring extensive travel, close quarters with people and animals, and millions of concentrated areas of troops on the move, this particular virus may not have reached global proportions.

In our present day, not only is travel faster, but more people are doing it. The average commuting American spends almost 30 minutes traveling to work, and almost 100 million Americans traveled outside the country for leisure in 2018. When outbreaks occur, the first things to drop off are travel, but the allure of deep discounts like $300 tickets to Europe and 86% off the cost of a cruise, still entice people to travel in large numbers.

Unlike our ancestors, some travel safety protocols like screening passengers and sanitation of shared spaces can reduce the rate of spread, anytime people are together in close quarters traveling for even short periods of time, rates of infection will increase. As we have seen in other countries when cities are quarantined and travel is restricted, some suppression of viruses can occur; however, we have learned from history the indisputable fact that travel does spread viruses very effectively. The second major lesson of the Spanish Flu is to avoid large gatherings.

In 1918, it took a person at least two days to travel across the United States by railroad. Today, a person can circumnavigate the entire planet by jet plane in forty-five hours– just slightly less than the same two days. Given the slow travel time of our ancestors, the rate of geographic spread was likely slowed; however, longer periods of time in close quarters with fellow travelers, likely resulted in a higher rate of community spread. So, when soldiers finally reached their destination back home or back on the front lines, there were more carriers of the virus. Had the world not been engaged in a major war, requiring extensive travel, close quarters with people and animals, and millions of concentrated areas of troops on the move, this particular virus may not have reached global proportions.

In our present day, not only is travel faster, but more people are doing it. The average commuting American spends almost 30 minutes traveling to work, and almost 100 million Americans traveled outside the country for leisure in 2018. When outbreaks occur, the first things to drop off are travel, but the allure of deep discounts like $300 tickets to Europe and 86% off the cost of a cruise, still entice people to travel in large numbers.

Unlike our ancestors, some travel safety protocols like screening passengers and sanitation of shared spaces can reduce the rate of spread, anytime people are together in close quarters traveling for even short periods of time, rates of infection will increase. As we have seen in other countries when cities are quarantined and travel is restricted, some suppression of viruses can occur; however, we have learned from history the indisputable fact that travel does spread viruses very effectively. The second major lesson of the Spanish Flu is to avoid large gatherings.

Avoid large gatherings and public places

When the governments actively seek to suppress the true facts about an outbreak, they put their populations at risk. In 1918, the city of Philadelphia, perhaps uninformed about the true threat of the Spanish Flu, sought to sell bonds to pay for the war effort through a parade. As the Great War raged and American doughboys fell on Europe’s battlefields, the City of Brotherly Love organized a grand spectacle. To bolster morale and support the war effort, a procession for the ages brought together marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliaries, and uniformed troops to promote Liberty Loans –government bonds issued to pay for the war. Within 72 hours of the event, every bed in the city’s 31 hospitals was filled with a sick patient. After a week, 4,500 people had died from the flu or its complications.

We now know with certainty that avoiding public gatherings reduces our exposure to a virus. Many businesses are already evaluating scheduled conferences, determining if meetings can better be accomplished virtually, beginning to offer paid sick leave to some employees, and finding ways to deliver products and services with minimal person-to-person interactions.

Today, we already see businesses curbing non-essential travel, schools closing for short periods of time, even the release of blockbuster movies being delayed, all in an effort to curb the spread of a virus. How effective these efforts will remain to be seen; however, the 1918 outbreak taught us a valuable lesson to avoid public gatherings if at all possible and whenever possible.

When the governments actively seek to suppress the true facts about an outbreak, they put their populations at risk. In 1918, the city of Philadelphia, perhaps uninformed about the true threat of the Spanish Flu, sought to sell bonds to pay for the war effort through a parade. As the Great War raged and American doughboys fell on Europe’s battlefields, the City of Brotherly Love organized a grand spectacle. To bolster morale and support the war effort, a procession for the ages brought together marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliaries, and uniformed troops to promote Liberty Loans –government bonds issued to pay for the war. Within 72 hours of the event, every bed in the city’s 31 hospitals was filled with a sick patient. After a week, 4,500 people had died from the flu or its complications.

We now know with certainty that avoiding public gatherings reduces our exposure to a virus. Many businesses are already evaluating scheduled conferences, determining if meetings can better be accomplished virtually, beginning to offer paid sick leave to some employees, and finding ways to deliver products and services with minimal person-to-person interactions.

Today, we already see businesses curbing non-essential travel, schools closing for short periods of time, even the release of blockbuster movies being delayed, all in an effort to curb the spread of a virus. How effective these efforts will remain to be seen; however, the 1918 outbreak taught us a valuable lesson to avoid public gatherings if at all possible and whenever possible.

Governments tell you what they want you to hear

The third major lesson of the Spanish Flu is that governments, seeking at all costs to avoid public panic and any disruption to public order, will knowingly and unknowingly suppress the truth and tell people what they want to hear. Like a parent that avoids certain topics or dances around a sensitive subject from an inquisitive child, governments avoid too heavy an expression of truth.

In 1918, governments didn’t want to show the weakness of their country or their fighting forces. The Spanish Flu is so named not because that was the epicenter, but because the country of Spain, neutral in that World War, had a free press that reported true cases and true accounts of the Influenza outbreak.

Today, as it was then, we can assume the actual numbers of infected individuals are much higher than what is available from government reports and government-controlled websites. In fact, some government officials and reports seem to be in direct contradiction of physicians and scientists. Constantly downplaying the significance of an outbreak, we can assume that the numbers are higher, the rate of spread may be higher, and sometimes even the actual death toll may be higher. Did a person die from the flu or complications from the flu, or a later bacterial infection resulting from a weakened condition after having recovered from the flu? How those numbers are reported actually determines the true mortality rate.

Governments and the mainstream media, while claiming to have your best interests in mind and claiming to be the definitive and most trusted source, do not always have a good sense of what is actually occurring. As in 1918, they can often just give patently false information.

The third major lesson of the Spanish Flu is that governments, seeking at all costs to avoid public panic and any disruption to public order, will knowingly and unknowingly suppress the truth and tell people what they want to hear. Like a parent that avoids certain topics or dances around a sensitive subject from an inquisitive child, governments avoid too heavy an expression of truth.

In 1918, governments didn’t want to show the weakness of their country or their fighting forces. The Spanish Flu is so named not because that was the epicenter, but because the country of Spain, neutral in that World War, had a free press that reported true cases and true accounts of the Influenza outbreak.

Today, as it was then, we can assume the actual numbers of infected individuals are much higher than what is available from government reports and government-controlled websites. In fact, some government officials and reports seem to be in direct contradiction of physicians and scientists. Constantly downplaying the significance of an outbreak, we can assume that the numbers are higher, the rate of spread may be higher, and sometimes even the actual death toll may be higher. Did a person die from the flu or complications from the flu, or a later bacterial infection resulting from a weakened condition after having recovered from the flu? How those numbers are reported actually determines the true mortality rate.

Governments and the mainstream media, while claiming to have your best interests in mind and claiming to be the definitive and most trusted source, do not always have a good sense of what is actually occurring. As in 1918, they can often just give patently false information.

Put the present day into historical context

To keep a level-head current perspective, we have to put the 1918 outbreak in its historical context. We are beginning to realize that the Spanish Flu was not the result of some super doomsday strain of a virus. While it certainly had a serious lethality to it, it’s now thought that many of the deaths were due to the development of bacterial pneumonia in the lungs weakened by influenza. The flu and complications after the flu can have serious consequences depending upon when a person is treated, how they are treated, and how much exposure risk they put other people during their infectious period.

The common treatments for the flu in 1918 were whiskey and enemas. To avoid the flu, people were encouraged to go outdoors. While fresh air and sunshine do have some virus-killing effects, and many an Irish grandmother would recommend a hot toddy to stave off the flu, these methods are less effective than the preventative measures and medicines in place today. In fact, it is thought that many of the deaths may have been linked to aspirin poisoning, and we know today not to give aspirin to a person with the flu because of Reye’s syndrome. We also know that large doses can lead to excessive bleeding, which was one of the symptoms of the Spanish Flu, by the way. Medical authorities at the time recommended large doses of aspirin of up to 30 grams per day. Today, about four grams would be considered the absolute maximum safe daily dose. In 1918, hand washing was not seen as a means to prevent the spread of a virus. Today, we know handwashing, sanitation, wiping down surfaces, self-quarantining, and avoiding close personal contact with people can all greatly decrease our chances of becoming exposed to a contagion.

Add to this that we have a number of medicines to prevent symptoms from becoming lethal that our ancestors did not, and a person today has a much higher rate of recovery from a novel virus that our ancestors did. Knowledge is power, and medical advances have allowed us to target sicknesses and their life-threatening symptoms more directly. Even some early intervention medicines like Tamiflu or the homeopathic remedies of Elderberry and the Zinc vitamin may help to reduce the duration of illness from a virus. It’s possible that granny’s hot toddy, with its cough suppressing honey and vitamin C, may actually work a little as well. Compared to the past, we know today that even staying hydrated well through a flu can speed our recovery time and prevent further complications once the virus has been eradicated from our bodies and we are recovering.

We also know that those most susceptible to the virus of 1918 were in their 20s and 30s. This may have been because that particular age group was heavily engaged in a World War, in close contact with each other, and, as a result of the use of gas warfare for the first time, often recovering from dramatically weakened lungs. Concentrating millions of troops created ideal circumstances for the development of more aggressive strains of the virus and its spread around the globe. Compared to today’s viruses, this same young age bracket appears to be only getting mild symptoms and some children no symptoms at all. Elderly individuals, however, are at the greatest risk today. Also, fortunately, we aren’t concentrating millions of individuals together in a war zone.

In short, when we put the Spanish flu in the proper historical context and then look at it through the lens of today, we can see that, if we prepare ourselves and treat ourselves properly, our chances of succumbing to a virus are much lower. It’s when the viruses are downplayed in seriousness and we fail to take proper precautions that we put ourselves most at risk.

To keep a level-head current perspective, we have to put the 1918 outbreak in its historical context. We are beginning to realize that the Spanish Flu was not the result of some super doomsday strain of a virus. While it certainly had a serious lethality to it, it’s now thought that many of the deaths were due to the development of bacterial pneumonia in the lungs weakened by influenza. The flu and complications after the flu can have serious consequences depending upon when a person is treated, how they are treated, and how much exposure risk they put other people during their infectious period.

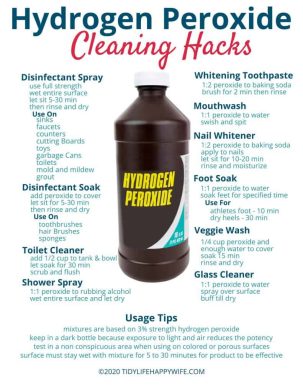

The common treatments for the flu in 1918 were whiskey and enemas. To avoid the flu, people were encouraged to go outdoors. While fresh air and sunshine do have some virus-killing effects, and many an Irish grandmother would recommend a hot toddy to stave off the flu, these methods are less effective than the preventative measures and medicines in place today. In fact, it is thought that many of the deaths may have been linked to aspirin poisoning, and we know today not to give aspirin to a person with the flu because of Reye’s syndrome. We also know that large doses can lead to excessive bleeding, which was one of the symptoms of the Spanish Flu, by the way. Medical authorities at the time recommended large doses of aspirin of up to 30 grams per day. Today, about four grams would be considered the absolute maximum safe daily dose. In 1918, hand washing was not seen as a means to prevent the spread of a virus. Today, we know handwashing, sanitation, wiping down surfaces, self-quarantining, and avoiding close personal contact with people can all greatly decrease our chances of becoming exposed to a contagion.

Add to this that we have a number of medicines to prevent symptoms from becoming lethal that our ancestors did not, and a person today has a much higher rate of recovery from a novel virus that our ancestors did. Knowledge is power, and medical advances have allowed us to target sicknesses and their life-threatening symptoms more directly. Even some early intervention medicines like Tamiflu or the homeopathic remedies of Elderberry and the Zinc vitamin may help to reduce the duration of illness from a virus. It’s possible that granny’s hot toddy, with its cough suppressing honey and vitamin C, may actually work a little as well. Compared to the past, we know today that even staying hydrated well through a flu can speed our recovery time and prevent further complications once the virus has been eradicated from our bodies and we are recovering.

We also know that those most susceptible to the virus of 1918 were in their 20s and 30s. This may have been because that particular age group was heavily engaged in a World War, in close contact with each other, and, as a result of the use of gas warfare for the first time, often recovering from dramatically weakened lungs. Concentrating millions of troops created ideal circumstances for the development of more aggressive strains of the virus and its spread around the globe. Compared to today’s viruses, this same young age bracket appears to be only getting mild symptoms and some children no symptoms at all. Elderly individuals, however, are at the greatest risk today. Also, fortunately, we aren’t concentrating millions of individuals together in a war zone.

In short, when we put the Spanish flu in the proper historical context and then look at it through the lens of today, we can see that, if we prepare ourselves and treat ourselves properly, our chances of succumbing to a virus are much lower. It’s when the viruses are downplayed in seriousness and we fail to take proper precautions that we put ourselves most at risk.

Expect a second and third wave

The biggest lesson we absolutely must learn from the Spanish Flu of 1918, is that the flu travels in waves. What we are seeing today may only be the first wave of a more dramatic wave yet to come. There were three significant waves of the Spanish flu. The death rates in the first of the year in 1918 were relatively low compared to the second wave during the typical flu season of that year–October through December. There was also a third wave in 1919 that was more lethal than the first but less so than the second.

We also know that when the typical flu season subsides in the northern hemisphere, the southern hemisphere’s flu season is ramping up, so a flu virus never truly phases out. Our ability to monitor, test for, and record the actual rate of infection is tremendously better than it was a hundred years ago. Gene sequencing allows us to determine if a virus has mutated. Today, we can determine if a potential outbreak’s threat is higher or lower at any given time. Our ability to see the second and third waves of a virus allows us some small amount of time to prepare for it.

History teaches us, however, that a second and third wave of today’s viruses are to be expected. They are imminent. Different strains of a virus never really die off and immunity is never a certainty. We should remain prepared, remain cautiously vigilant, and continue to practice reasonable precautions like frequent hand washing, avoiding touching our faces, and keeping the surfaces of our homes like doorknobs clean. We should avoid public venues and public gatherings whenever we are seeing a rise in infectious spreading. We should encourage others to stay home when ill and self-quarantine ourselves when we may be coming down with something. We should have medicines on hand to mitigate the lethal consequences of illnesses, and we should stay hydrated. Each single precaution we take cannot guarantee we won’t get the flu; however, each precaution taken, cumulatively, can put the odds of staying healthy in our favor.

Conclusion

To summarize the points in this blog, if history teaches us one thing, it’s that when we are well-informed and adequately prepared, we increase our odds of survival. The 1918 outbreak of the Spanish Flu taught us that viruses spread more quickly and prolifically through traveling and close proximity to others. It should teach us to avoid unnecessary gatherings and to question and evaluate the necessity of scheduled gatherings during times of increased risks. We should know that governments and mainstream media are not going to provide the unvarnished truth, so we should allow ourselves to read into the reports a little more than what we are being presented, and we should be informed enough to be able to draw our own conclusions about our relative safety from the facts we can determine.

Furthermore, the lessons from a hundred years ago should teach us that we need to look at the events of the past through the proper focus of the lens of today. From a viruses’ prevalence to mortality rates, to prevention and treatment, advancements in information, medications, and public knowledge all equip us with a greater ability to combat the spread and effects of a virus.

Finally, we know with absolute certainty that viruses don’t really die off. While they may mutate over time to less effective strains, while we may develop some reasonably effective vaccines over time, while we can leverage science and knowledge to minimize exposure and risk, it is certain that subsequent waves of any virus can be expected.

If you found this blog informative and helpful, please feel free to like and share it with your friends, family, and community. If you have any comments or anything you would like to share, please feel free to leave a comment in the section below.

The biggest lesson we absolutely must learn from the Spanish Flu of 1918, is that the flu travels in waves. What we are seeing today may only be the first wave of a more dramatic wave yet to come. There were three significant waves of the Spanish flu. The death rates in the first of the year in 1918 were relatively low compared to the second wave during the typical flu season of that year–October through December. There was also a third wave in 1919 that was more lethal than the first but less so than the second.

We also know that when the typical flu season subsides in the northern hemisphere, the southern hemisphere’s flu season is ramping up, so a flu virus never truly phases out. Our ability to monitor, test for, and record the actual rate of infection is tremendously better than it was a hundred years ago. Gene sequencing allows us to determine if a virus has mutated. Today, we can determine if a potential outbreak’s threat is higher or lower at any given time. Our ability to see the second and third waves of a virus allows us some small amount of time to prepare for it.

History teaches us, however, that a second and third wave of today’s viruses are to be expected. They are imminent. Different strains of a virus never really die off and immunity is never a certainty. We should remain prepared, remain cautiously vigilant, and continue to practice reasonable precautions like frequent hand washing, avoiding touching our faces, and keeping the surfaces of our homes like doorknobs clean. We should avoid public venues and public gatherings whenever we are seeing a rise in infectious spreading. We should encourage others to stay home when ill and self-quarantine ourselves when we may be coming down with something. We should have medicines on hand to mitigate the lethal consequences of illnesses, and we should stay hydrated. Each single precaution we take cannot guarantee we won’t get the flu; however, each precaution taken, cumulatively, can put the odds of staying healthy in our favor.

Conclusion

To summarize the points in this blog, if history teaches us one thing, it’s that when we are well-informed and adequately prepared, we increase our odds of survival. The 1918 outbreak of the Spanish Flu taught us that viruses spread more quickly and prolifically through traveling and close proximity to others. It should teach us to avoid unnecessary gatherings and to question and evaluate the necessity of scheduled gatherings during times of increased risks. We should know that governments and mainstream media are not going to provide the unvarnished truth, so we should allow ourselves to read into the reports a little more than what we are being presented, and we should be informed enough to be able to draw our own conclusions about our relative safety from the facts we can determine.

Furthermore, the lessons from a hundred years ago should teach us that we need to look at the events of the past through the proper focus of the lens of today. From a viruses’ prevalence to mortality rates, to prevention and treatment, advancements in information, medications, and public knowledge all equip us with a greater ability to combat the spread and effects of a virus.

Finally, we know with absolute certainty that viruses don’t really die off. While they may mutate over time to less effective strains, while we may develop some reasonably effective vaccines over time, while we can leverage science and knowledge to minimize exposure and risk, it is certain that subsequent waves of any virus can be expected.

If you found this blog informative and helpful, please feel free to like and share it with your friends, family, and community. If you have any comments or anything you would like to share, please feel free to leave a comment in the section below.